Email: stephane.gaessler@inha.fr

Email: kmalich@hse.ru

Email: pech_archistory@mail.ru

Revised 25 January 2022

Accepted 25 November 2022

Available Online 10 January 2023

- DOI

- https://doi.org/10.55060/s.atssh.221230.019

- Keywords

- World fairs

Expo

Russian and Soviet architecture

Modern architecture

Cultural diplomacy - Abstract

This article is dedicated to Russian and Soviet pavilions at world fairs of the first half of the 20th century, which is one of the most important topics of both history of architecture and international relations. The article brings to light unpublished episodes of Russian and Soviet participation at the international exhibitions. The pavilions were at the same time the screen and show-window of the country, which formed its image worldwide. The study is focused on their ideological role and realization aspects, analyzing previously unpublished and underexplored project materials and archival documents, with special attention to the interaction between the parties, cultural diplomacy, contacts with emigrants and local context.

- Copyright

- © 2022 The Authors. Published by Athena International Publishing B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Even though the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) pavilions at the international exhibitions in Paris in 1925 and 1937, designed respectively by Konstantin Melnikov and Boris Iofan, are widely known both in Russia and abroad, the buildings and projects of Russian and then Soviet pavilions at other major international exhibitions in European cities remain poorly studied. Russian pavilions at the Expo’s in Rome and Turin in 1911, in Monza in 1927, at the Milan Fair in 1926 and the Triennale in 1933, the process of building the Melnikov pavilion in Paris and the collaboration of Berthold Lyubetkin and his other compatriots are still underexplored.

Since the Industrial Revolution, world exhibitions, as well as major international exhibitions of fine art, have occupied a key place in culture and have had a significant impact on culture in individual countries.

The tradition that developed in the 19th century gave the exhibition pavilion the status of a manifesto of national culture. This genre of architecture cannot be considered in isolation from the topic of constructing national identities, even if we are talking about a historical period when accents changed and classical nationalism gave way to other political ideologies.

2. LONG RESEARCH FOR “IDENTITY”

It is well known that the successful representation of national artistic innovations at exhibition venues can have a serious impact on foreign viewers. For example, the so-called “Russian modern”, especially in its Moscow version, was strongly inspired by the impressions of the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900. “In Moscow, in the mansions of Gallophils, in merchant families of the new formation, along with Parisian new hats, it was considered fashionable <...> to acquire foreign furniture or imitate the decadent ‘new style’ “, the prominent memoirist Prince S.A. Shcherbatov commented on this fact [1].

On the other hand, the demonstration of Russian “identity” at international exhibitions of the second half of the 19th century was spectacular, when the image of a fabulous terem, hut or boyar chambers was diligently played out in the pavilions of the Russian Empire. “Civilized France was surprised that the barbarians have a style, and moreover an original one”, the commissar of the Russian department at the World Exhibition of 1867, the artist V.G. Schwartz, noted with satisfaction [2]. “Russian style”, which was offered at the exhibitions of 1867, 1873 and 1878, attracted Europeans so much that it became possible, for example, “Russian Hut” at the National Exhibition of 1881 in Milan, designed by architect C. Formenti as pavilion for a wine merchant, or “House in the Russian Style of the 15th Century”, presented within the framework of Charles Garnier's project “Habitation of Humanity” at the World Fair in Paris in 1889 [3,4].

The turn of the century did not bring a radical change: in 1900 in Paris, Russia was represented by the fake “Kremlin” of the Pavilion of the Russian Provinces of the court architect R.F. Meltzer and the deliberately theatrical “Russian Village”, a complex of four log buildings which housed handicrafts of peasant craftsmen, executed according to drawings by famous artists [5]. Proposed here by the artist K.A. Korovin and the architect I.E. Bondarenko, Russian-style modernization met the expectations of the French public, but by and large fit into the mainstream of tradition, as well as the “Russian Town” in Glasgow which in 1902 brought its creator F.O. Shechtel the title of Academician of Architecture. However, by the beginning of the second decade of the new century, the situation had seriously changed. In the architecture of the Russian Empire, the peak of the popularity of Art Nouveau, associated to the greatest extent with French, Austrian and Scandinavian influences, passed quickly enough. Around 1910, it was replaced by nostalgic neoclassicism, inspired by Russian manors and urban ensembles of a century ago, not without the influence of historical dates like the centenary of the Patriotic War. This metamorphosis of taste preferences was reflected in the choice of the style of the pavilions of Russia at the exhibitions in Rome and Turin in 1911. Both were dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the unification of Italy, the first was dedicated to art, the second to the success of industrialization.

Especially interesting is the history of the creation of the pavilion at the Rome exhibition, the Russian participation in which was entrusted to the Imperial Academy of Arts to prepare. At first it was supposed to be limited to the arrangement of the Russian department, but when it became clear that the leading world powers (Great Britain, Germany, France and Austria-Hungary) were performing with separate pavilions, prestige considerations demanded the same from Russia. Judging by design materials preserved in the Shchusev Museum of Architecture and in the Museum of the Academy of Arts, the Academy attracted several architects to develop proposals – M.M. Peretyatkovich, I.V. Zholtovsky, V.A. Shchuko dictated the stylistic solution of the pavilion – in neoclassical style. The details of Peretyatkovich's participation are not clear yet; there is only his signature sketch. There are no indications of a competition for pavilion projects, apparently, work was carried out consistently. In any case, this can be seen in the example of Zholtovsky and Shchuko.

In December 1909, an agreement was reached between Zholtovsky and F.G. Berenstam, a representative of the Academy, to carry out design work. The surviving design materials include perspective views, plans and an orthogonal image of the facade for several versions of the pavilion. However, the work was delayed by Zholtovsky, and the order was delegated to Shchuko in March 1910 [6]. It was his project that was approved by Emperor Nicholas II and implemented by Italian contractors.

The Shchuko project best embodied the formula of classics as a national treasure of Russia, since in it the architect combined the composition of the Tsarskoye Selo Cold Baths by Charles Cameron with the Empire interpretation of the order in the spirit of D. Gilardi and copies of sculptures by the Mining Institute of A.N. Voronikhin. It is curious that Shchuko's predecessors, Peretyatkovich and Zholtovsky, solved the composition in a completely different way, but similar to each other: as a compact domed building. If in Peretyatkovich's sketch you can see a reference to the Pavlovsk Palace of the same Cameron, then Zholtovsky painted a building that almost copies the villa Rotunda. Perhaps the intention of this architect to show the Italian Renaissance in Rome on behalf of Russia also played a role in the fate of his project, seeming to customers insufficiently “patriotic”.

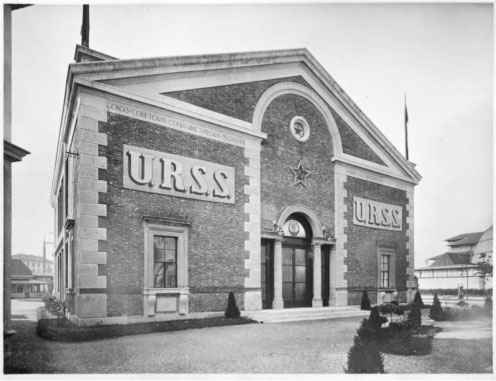

15 years later, Zholtovsky, already commissioned by the Trade Representation of the USSR at the VII International Exhibition in Milan, designed another pavilion, adhering to the same Palladian paradigm (Fig. 1). The organizers of the Milan Industrial Fair invited the Soviet side to build a permanent building for their expositions, transmitting their invitation through the Italian Embassy in Moscow: “I ask you to keep the flame of the widest Russian participation in the future exhibition and insist that Russia build a pavilion for itself, in full confidence that Italy is characterized by hospitality in a much higher and nobler form than in other countries, even if our country is not republican” [7].

The figure of the plan of the realized pavilion was the so-called “Functional Square” of Zholtovsky, a rectangle of which the length of the sides reproduces the proportion of the golden section (528:472). The simplicity of the three-dimensional composition (the building is blocked by two slopes) is complemented by the equally “obvious” solution of the side facades, which are almost completely glazed. The facades, which can be considered “main” and “rear”, are decorated using the serliana motif: in the first case the entrance portal is decorated with it, and in the second the skylight window. Originally, the main facade was designed as a fairly accurate quotation of the Villa Valmarana in Vigardolo near Vicenza (a. Palladio, 1541–1543?), but in the implemented version, the similarity was not so striking [6].

From 1923–1926, the architect was on a business trip abroad through the People's Commissariat of Education, although there are grounds to consider it an attempt to emigrate. At the same time, Zholtovsky's name was glorified by the success of his work for the All-Russian Agricultural and Industrial Art Exhibition of 1923, where he owned the master plan of the complex and several of the most significant pavilions, including the design of the entrance. In 1925, at the International Exhibition of Decorative Art in Paris, an international jury awarded him, as an exhibitor of the USSR Department of Architecture, a gold medal for these objects.

I.V. Zholtovsky. USSR Pavilion. Milan Fair (1926).

As known, the Soviet pavilion of K.S. Melnikov became a favorite of the exhibition. However, Russian artists in France had privately approached Zholtovsky, who lived in Italy, “with a request to take part in the construction of the Russian pavilion”, but a year earlier, when diplomatic relations between USSR and France did not exist and Russian art at the exhibition could only be presented by emigrant circles [8].

It is still unclear whether the architect accepted this invitation and started thinking about the pavilion project. In the folder of design materials of the Milan Pavilion in the funds of architectural graphics of the GNIM, sheets representing construction options in the “Russian style” are stored (Fig. 2). In the museum's catalog, they are attributed as preliminary sketches for the same Milan [9], but from the side of Zholtovsky, the intention to present the Soviet exposition in the sacramental “terem” would look too simple-minded. Such national-romantic images seem to be more in tune with emigrant sentiments, as shown, for example, by expositions of Decorative Arts Exhibitions in Monza in 1923 and 1925, made by emigrant artists. Do these drawings by Zholtovsky refer to the failed Paris pavilion? This topic undoubtedly deserves a more detailed study.

I.V. Zholtovsky. Design for the USSR pavilion at the Milan Fair (?) of 1926; unrealized version. In: Shchusev Museum of Architecture (Inv. P Ia-9265/3).

3. BUILDING SOVIET PAVILIONS ABROAD: THE BACKSTAGE

Participation in large international exhibitions was not the only way of interaction between the USSR and the Western world. If large-scale reviews were rare, and the process of their preparation was quite bureaucratic, then possibilities of operational work on the spot gave the Soviet trade missions much more opportunities. Moreover, after the revolution it was necessary to solve a number of economic issues, one of which was the popularization of Soviet goods. The Soviet government pursued an active foreign trade policy. Trying to overcome isolation, and at the same time to present the Western public the advantage of a progressive social order, officials tried to use a convincing communication design strategy for the Western viewer. The USSR Trade Mission in Paris was actively working, trying to participate in French trade exhibitions. After the success of K. Melnikov's pavilion in 1925, the trade mission ordered a stylistically similar pavilion to the Belarusian engineer Volodko.

Franz Jourdain (a staunch communist who sympathized with the Soviet Republic) advised the trade mission to take Berthold Lubetkin as assistant, as he sometimes worked for them as an interpreter [10]. Lubetkin had to figure out the idea of Volodko, then find suitable local materials, implement the project and accompany the design at all trade shows.

Lubetkin gladly took up a new job for the trade mission. As he wrote in the explanatory note, “After reviewing the project and the price of construction, we jointly came to the conclusion that the costs of building the pavilion will be large and will not justify themselves with a one-time construction. Therefore, I was assigned to study the project of a collapsible pavilion, based on the main ideas of Comrade Volodko… The supervision of the construction of the pavilion entrusted to us can serve as a sufficient guarantee of the careful handling of the material by the workers during installation and disassembly, however, before each new exhibition we will have to check the condition and strength of the material and give a written report on it.” [11]

In an explanatory note on 9 August 1929, the architect writes that since costs of a single construction of the pavilion are impractical, he came with a demountable structure and slightly changed the proportions. As a result, the shape and size of the structure could vary depending on the number of exhibits, and the structure could withstand 4 installations, despite its “complex, non-web-like nature”. From 1928–1931, the Soviet pavilion visited exhibitions in Strasbourg, Marseille (Fig. 3), Bordeaux and Nancy.

Lubetkin's duties included the installation of the pavilion, negotiations with the contractor, static calculations, checking the foundations and installation of the supporting structure, painting, checking contractors' accounts, monitoring all work. In Strasbourg, the main exposition manager of the Soviet pavilion was G. Kifkutsan, with whom Lubetkin became friends and later corresponded, discussing the possibility of returning to the USSR. Another Soviet official, whom Lubetkin later recalled, was a “tough woman called Zheleznyak; she kept bragging about how, during the Civil War, she had cut a white guard vertically in half” [12]. But, apparently, despite his formidable appearance, Zheleznyak was satisfied with the work of the young specialist. In any case, all the certificates of the Soviet trade mission signed by her hand note that the exhibition bureau was satisfied “both from the technological and artistic side” [13].

Together with another emigrant from Russia, Vladimir “Bobka” Rodionov1, Lubetkin took part in another exhibition. He received this order in an absurd way. Gaston Trélat, director of the École Spéciale d'Architecture where Lubetkin studied, at the first meeting looking at Lubetkin's trousers decided that he had come from Mexico. Therefore, when representatives of Cameroon turned to Trélat with a request to recommend someone who could build a small pavilion for the International Colonial Exhibition, the professor remembered his “exotic” student and handed the order to Lubetkin. Trying to build an “African” structure in the colonial spirit, Rodionov and Lubetkin got cow manure, but the plastic qualities of the material did not allow the structure to be given the necessary shape. They had to use more expensive clay. By the way, Lubetkin himself lived in the famous “Beehive” (La Ruche) for some time in the mid-1920s, for which the sculptor Alfred Boucher bought a number of buildings after the dismantling of the Paris World's Fair in 1900, including a wine pavilion designed by Gustave Eiffel.

B. Lubetkin. Soviet pavilion in Marseille (1931, postcard).

During the exhibitions, Lubetkin had the opportunity to get acquainted with other young European architects. For example, in Strasbourg he found Theo van Doesburg working on his famous Café Obette. Soon, however, the ideas of avant-garde architecture and international pan-European culture (not without the influence of the success of Soviet pavilions) began to irritate those European customers who were afraid of the “red threat”. In the eyes of conservatives, many representatives of functionalism were discredited by the fascination with socialist trends, and Soviet officials later changed the nature of self-presentation.

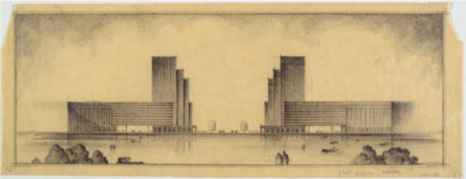

International exhibitions were also the occasion for the Soviet architects to go abroad. Thus, V.K. Oltarzhevsky, in 1924, requested an Italian visa as a “delegate to the Venice Biennale”, and among the goals he indicated “the study of modern construction equipment, as well as garden cities and workers' settlements” [14]. After leaving the country, the architect returned to the USSR only in 1935, after 10 years of study and work in the USA, including on the construction of skyscrapers. However, some documents reveal that Oltarzhevsky spent some time in the French capital from 1926–1931. Among them there is his project for the close competition by invitations for the Design of the western part of Axe Historique of Paris, sponsored by Russian-born mecenate Léonard Rosenthal, now kept by the Shchusev State Museum of Architecture (Fig. 4).

V.K. Oltarzhevsky. Project for Marshal Foch Square Competition (Paris, 1930). In: Shchusev Museum of Architecture (Inv. ОФ-1560/125).

4. ARCHITECTS FROM THE USSR AT INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS: MONZA-MILANO TRIENNALE CASE

As can be seen, the Soviet Embassies often involved emigrant architects or national professionals who stayed abroad at the moment to work on the exhibitions. Thus, Georgy Golts, a Vkhutemas fellow in Italy in 1927, was involved in the design of the Soviet stands at the 3d Monza Biennale of Decorative Arts. In 1930, the USSR took part in the Milan Triennial, but the exposition did not receive a special design project.

In 1933, Konstantin Melnikov was invited to participate in the next exhibition, held in a new, specially built building (architect Giovanni Muzio). His stand was to be presented at the exposition of the “Masters of Modern Architecture”, the architects who – according to the curators Gio Ponti, Mario Sironi and Carlo Felice – made the greatest contribution to the formation of the architecture of the modern movement: Adolf Loos, Peter Behrens, Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier and others [15] (Fig. 5).

Exhibition “Maestri del Movimento Moderno” at the Milan Triennale V in 1933. Melnikov’s stand is the 3rd from the right. In: Archivio Fotografico, Triennale di Milano (Inv. TRN_V_03_0133).

The architect himself had no opportunity to come. The exposition of his projects was designed by the organizing committee lead by Gio Ponti and received a noticeable resonance in the professional press. “Casabella” magazine published a review of the exhibition, placing Club Rusakov (1927–1929) on the cover among other buildings of his contemporaries (1933, no. 6), and the director of the Triennial and architectural critic Agnoldomenico Pica wrote about Melnikov's “fearless acrobatics” ([16], pp. 40).

The USSR exposition stand was also made by the organizers of the Triennial. A collage of constructivist buildings, however, was accompanied by a text sent by the staff of the Soviet embassy, reflecting a deep distance from the principles that once Melnikov expressed. “The apology of naked technology ... does not inspire Soviet architects,” it was reported. “Soviet architecture does not deny the great classical past ... the great traditions of the past must be combined with the new capabilities of modern technology” [17]. As an example of new aspirations, the project of the Palace of Soviets in Moscow by B.M. Iofan, freshly approved for the construction after international competition, was cited. This exhibition was essentially the last for the architecture of the Soviet avant-garde. Further Soviet expositions at world exhibitions were shown in pavilions designed by Iofan, the just mentioned protagonist of the architecture of the “assimilation of heritage”, who in his turn in the early 1920s, while living in Italy, worked as a “local” architect of the first Soviet foreign exhibitions.

5. CONCLUSION

As the research has shown, the architecture of the exhibition pavilions and the circumstances of their implementation were not only the embodiment of actual aesthetic programs, but also a document telling about the life and work of Soviet architects abroad and the interaction of emigration with Soviet representations. The specific architectural language didn’t have fixed ideological connotation, it could be changed according to local context, but at the same time it has always had a strong ideological charge. The study always show that the pavilions were often realized not by the professionals from USSR, but by Russian émigré, even if they left their homeland after the Revolution (as in case of Berthold Lubetkin). It also shows that sometimes exhibitions of USSR were made by local organizers of fairs, with the lack of interest of Soviet authorities (as in case of Melnikov’s show and USSR panel at the V Triennale in Milan).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the grant for “Cooperation of the Russian Foundation for Basic Research and the National Center for Scientific Research of France (International Emerging Actions)”, project no. 21-512-15002, dir. by Anna Vyazemtseva (Russia) and Jean Battiste Minnaert (France).

Footnotes

Archbishop Seraphim (Seraphin Rodionov), 1905-1997, artist, icon painter. Emigrated to France in 1923. Participated in group exhibitions, in particular in the Exhibition of Russian Artists in the cafe “La Rotonde” (1925).

REFERENCES

Cite This Article

TY - CONF AU - Stéphane Gaessler AU - Ksenia Malich AU - Ilya Pechenkin AU - Anna Vyazemtseva PY - 2023 DA - 2023/01/10 TI - Russian and Soviet Pavilions for International Exhibitions in Europe: New Findings BT - Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Architecture: Heritage, Traditions and Innovations (AHTI 2022) PB - Athena Publishing SP - 147 EP - 152 SN - 2949-8937 UR - https://doi.org/10.55060/s.atssh.221230.019 DO - https://doi.org/10.55060/s.atssh.221230.019 ID - Gaessler2023 ER -